Bigodi wetland sanctuary, Uganda, 2017.

Bigodi wetland sanctuary, Uganda, 2017.

The Village Weaver is one of the most common, widespread weaver species. It is larger than most weavers, with red eyes in both sexes and a heavy black bill. The breeding male has the head mainly black, the nape, hindneck and breast below the black throat are chestnut. The back is spotted yellow. The breeding female is yellow below, and whiter on belly. The non-breeding birds are duller than the breeding female.

The Village Weaver inhabits bushy savanna, riverine woodland, wetlands, cultivated areas, rural villages, urban and suburban gardens, and villages and clearings in the forest. It is frequently associated with human habitation in west and central Africa. It is absent from arid regions, dense forests, and miombo woodland.

Its diet is seeds, including grass seeds and cultivated cereals. It is regarded as a pest in rice-growing areas, and also damages maize, sorghum and durra crops. It also feeds on fruit, nectar, and insects, such as beetles, ants, termites and their alates, grasshoppers, mantids, caterpillars, and bugs. It forages by gleaning vegetation, including tree trunks.

The Village Weaver is gregarious, being found in large flocks and in the non-breeding period joins large communal roosts.

It is highly colonial, with more than 200 nests in a single tree and colonies in excess of 1000 nests. The Village Weaver is polygynous, with up to five females simultaneously on the territory of a male, and up to seven during a season. Females may change mates in a season. Larger colonies appear to be more attractive to females, with a higher proportion of females per male.

When females enter a colony, males hang below their nest entrances while giving nest-invitation calls and flapping their wings to show the yellow underwings. The nest is spherical, sometimes with a very short entrance tunnel. The nest is woven by the male within a day, generally from strips torn from reed or palm leaves.

The male often includes a ceiling layer of broad leaves. The female lines an accepted nest with leaves, grass-heads and some feathers. Nests are suspended from drooping branches. A single male may build more than 20 nests in a season, and unused or old nests are regularly destroyed to make space for new nests. Empty nests may be occupied by other animals, including snakes, wasps, mice and bats, and nests may be used for breeding by a wide variety of species including Cut-throat Finches.

The eggs are white, pale green or blue, either plain or variably marked with red-brown speckling. Incubation is by the female only, for about 12 days. The chicks are usually fed by the female alone, but males in some parts help. Female Village Weavers recognize their own egg pattern, which is constant throughout her life, and discriminate against non-matching eggs. Nest predators include snakes, especially boomslang Dispholidus typus, monkeys and baboons, crows and raptors.

The longevity record is 14 years in the wild.

#Birdifeastafrica

#Earthshots

#Visitugandarwandatanzania.

Bushbucks are one of the most widespread kinds of African antelopes. Their small size, coloring, and reclusive behavior help them survive close to human settlements and in very small habitats. Bushbuck horns have a single twist and smooth edges. This design is well-suited to their preference for dense habitat, as the horns do not hinder their escape from predators.

Bushbucks are one of the most widespread kinds of African antelopes. Their small size, coloring, and reclusive behavior help them survive close to human settlements and in very small habitats. Bushbuck horns have a single twist and smooth edges. This design is well-suited to their preference for dense habitat, as the horns do not hinder their escape from predators.

Although bushbucks usually live alone, they occasionally spend time in pairs or even in small groups of adult females, adult females with young, or adult males. A unique social structure is exhibited by bushbucks In Uganda. There, the female young remain with their mothers throughout their lives, and adult females organize themselves into matrilineal clans. Each related group maintains and defends a home range against unrelated females. Related females also engage in grooming and other social activities. Males leave their mother’s home range to join a bachelor herd when they are six months old and fight other male groups to gain territory.

Bushbucks spend most of their time eating, ruminating, resting, and moving. They are most active at dawn and dusk, though this varies based on season, age, and sex. Males are often combative. A male will first feign an attack by lowering his horns to the ground, but if he and his opponent are closely matched, they will lock horns and try to stab each other’s sides. While female bushbucks can be aggressive toward other females, they tend to fight much less than males. Bushbucks have a keen sense of smell. When either a male or a female senses a predator in the distance, they freeze and drop to the ground, keeping their head and neck against the earth until the danger passes.

If the predator is close, a bushbuck will emit a bark and flee into the bush with its tail raised.

Bushbucks are solitary creatures that communicate mainly through scent-marking rather than vocalization, although they occasionally emit a bark to warn of danger. A male bushbuck signals a challenge to another male by adopting a rigid walk, raising his head, arching his back, and lifting his tail. If the opponent is an equal match, he takes up a similar posture and the two circle one another; if the opponent submits, he keeps his head low and licks the dominant male. Some researchers think males may bark to indicate their status to another bushbuck.

Bushbucks are browsers. They eat a range of herbs and young leaves from both shrubs and trees throughout the day and night. They also raid farms and plantations to eat crops.

During courtship, the male nuzzles and licks the female, strokes her back with his cheeks, and presses his head or neck against her. If the female accepts his advances, the male guards her against any other eager males. Female bushbucks gestate for 24 to 35 weeks and usually bear a single calf, though occasionally they have twins. Females give birth in dense thickets, where the calves remain for up to four months while their mothers leave to graze. A male’s horns begin to emerge at seven months. Males reach sexual maturity at ten months, but most do not breed until they are two years old. Females reach maturity between 14 and 19 months and can give birth every year. @GodfreyT

#Interiorsafaris East Africa

#Africa #Uganda #Fauna #Antelope #Bushbuck

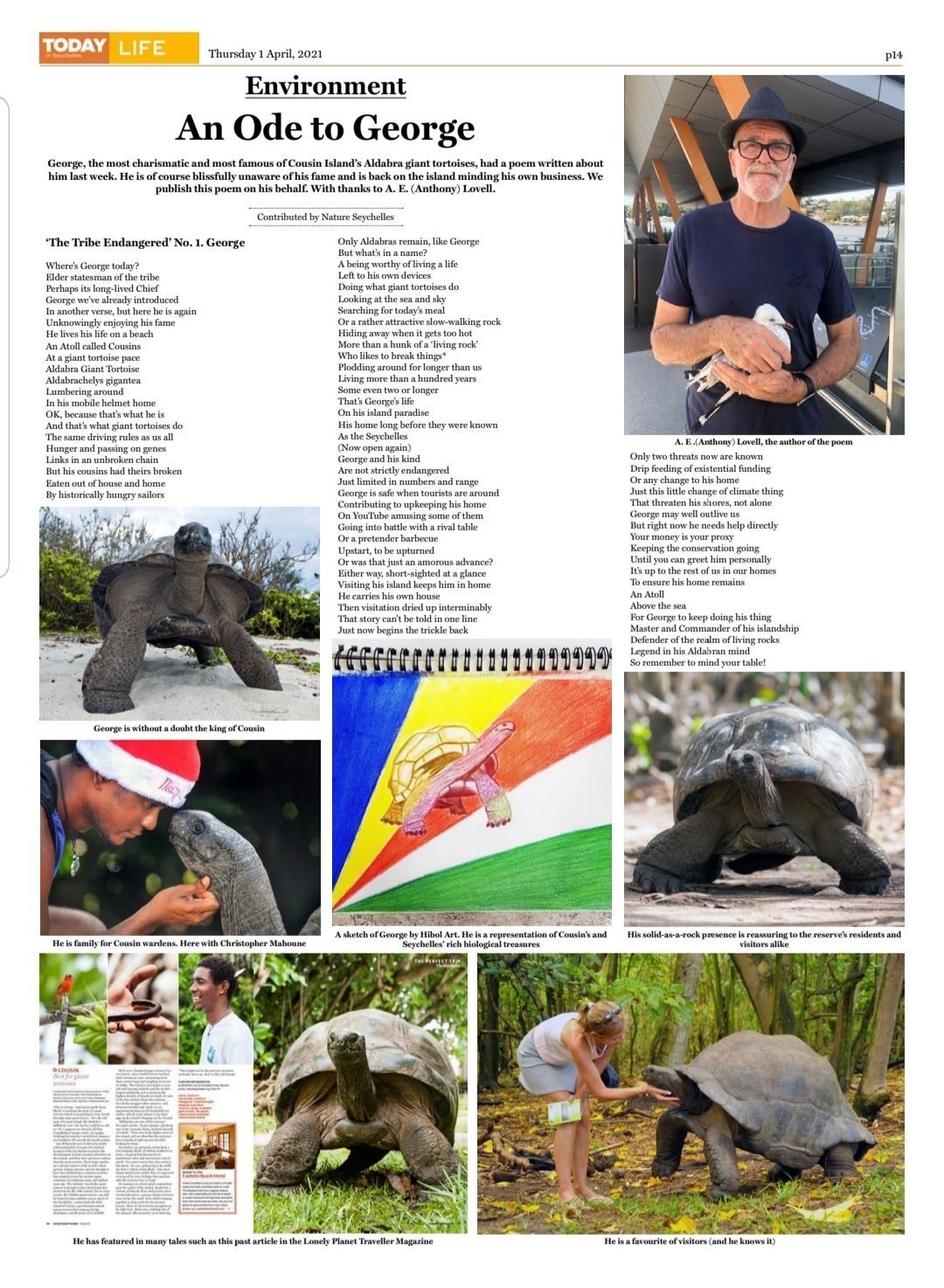

‘The Tribe Endangered’ No. 1. George

Where’s George today?

Elder statesman of the tribe

Perhaps its long-lived Chief

George we’ve already introduced

In another verse, but here he is again

Unknowingly enjoying his fame

He lives his life on a beach

An Atoll called Cousins

At a giant tortoise pace

Aldabra Giant Tortoise

Aldabrachelys Gigantea

Lumbering around

In his mobile helmet home

OK, because that’s what he is

And that’s what giant tortoises do

The same driving rules as us all

Hunger and passing on genes

Links in an unbroken chain

But his cousins had theirs broken

Eaten out of house and home

By historically hungry sailors

Only Aldabras remain, like George

But what’s in a name ?

A being worthy of living a life

Left to his own devices

Doing what giant tortoises do

Looking at the sea and sky

Searching for today’s meal

Or a rather attractive slow-walking rock

Hiding away when it gets too hot

More than a hunk of a ‘living rock’

Who likes to break things*

Plodding around for longer than us

Living more than a hundred years

Some even two or longer

That’s George’s life

On his island paradise

His home long before they were known

As the Seychelles

(Now open again)

George and his kind

Are not strictly endangered

Just limited in numbers and range

George is safe when tourists are around

Contributing to upkeeping his home

On YouTube amusing some of them

Going into battle with a rival table

Or a pretender barbecue

Upstart, to be upturned

Or was that just an amorous advance?

Either way, short-sighted at a glance

Visiting his island keeps him in home

He carries his own house

Then visitation dried up interminably

That story can’t be told in one line

Just now begins the trickle back

Only two threats now are known

Drip feeding of existential funding

Or any change to his home

Just this little change of climate thing

That threaten his shores, not alone

George may well outlive us

But right now he needs help directly

Your money is your proxy

Keeping the conservation going

Until you can greet him personally

It’s up to the rest of us in our homes

To ensure his home remains

An Atoll

Above the sea

For George to keep doing his thing

Master and Commander of his islandship

Defender of the realm of living rocks

Legend in his Aldabran mind

So remember to mind your table!

A.E.(Anthony) Lovell