Continued from last week, this week we count down from 5 to 1.

5. Tooth-billed Pigeon

A relative of the extinct dodo, tooth-billed pigeons are disappearing at an alarming rate. They only live in Samoa and are currently fewer than 400 left in the wild, with no captive populations to help conservation efforts. They are elusive birds, very rarely seen. Even though illegal today, hunting has played a huge part in their decline, along with the main threat being habitat loss due to agriculture, or natural causes likes cyclones or trees.

4. Gharial

Gharials are fish-eating crocodiles from India. They have long thin snouts with a large bump on the end which resembles a pot known as a Ghara, which is where they get their name. They spend most of their time in freshwater rivers, only leaving the water to bask in the sun and lay eggs. There are only around 200 left in the wild. Their decline is due to several issues, though all human-made. Habitat loss, pollution and entanglement in fishing nets pose as some of the biggest threats.

3. Kakapo

The kakapo, also called owl parrot, is a species of large, flightless, nocturnal, ground-dwelling parrot. The total known adult Kakapo population is 209, all of which are named and tagged, confined to four small islands off the coast of New Zealand that have been cleared of predators. A kakapo’s natural reaction is to freeze and blend in with the background when threatened. It is effective against predators that rely on sight to hunt but not smell.

2. Amur Leopard

Amur leopards are one of the world’s most endangered big cats. They are on the IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. In 2015, there were only around 90 Amur leopards left within their natural range. That number is now estimated to be less than 70. Like all species on the endangered list, humans are their biggest threat. Their beautiful coats are popular with poachers as are their bones which are sold for use in traditional Asian medicine. They are also at risk from habitat loss due to natural and human-made fires.

1. Vaquita

The vaquita is both the smallest and the most endangered marine mammal in the world. It has been classified as Critically Endangered by the IUCN since 1996, and in 2018, there were only around 15 vaquitas left. The latest estimate, from July 2019, suggests there are currently only 9. Their biggest threat is from the illegal fishing of totoaba, a large fish in demand because of its swim bladder. Vaquitas accidentally end up entangled in the gillnets set for totoaba and drown because they can no longer swim to the surface to breathe.

The death of hundreds of elephants in Botswana has been an unsolved mystery for a long time during this pandemic in Botswana. Most of these have shown the symptoms of dizziness and walking in circles before dropping dead face-first. Government officials quote that 281 elephants have been verified to be dead with this bizarre behavior, but the conservationists and the NGOs claim that the death toll is much higher.

Initially, wild life experts have omitted the possibility of tuberculosis and believe that the cause is beyond the known diseases. Though the death number does not sound serious in population perspective, it is absolutely critical to complete the diagnosis and have accurate results in order to avoid any foul play or before elephants succumb to more of such mysterious deaths.

Botswana has an estimated 130,000 Savanna elephants and is considered to be one of the last strongholds of species in Africa. The earlier estimations were to be around 350,000 and ivory poaching in 20th century has reduced the species to one third of them today. The thousand-square-mile to the northeast of Okavango Delta, which has witnessed the deaths of elephants has around 18,000 elephants roughly. The wildlife experts and veterans believe that the possible causes could be the ingestion of toxic bacteria into the water, viral infection from rodents in the area or a pathogen infection. Conservationists are also considering the possibility of poisoning by humans.

The investigating officials of the Botswana government had sent for the testing to the laboratories in Zimbabwe, South Africa, US and Canada as well. The wild life department made a press release that the deaths are probably due to natural toxins.

However, the officials have confirmed that the conclusion could not be made about the cause yet. Authorities have so far ruled out anthrax, as well as poaching, as the tusks were found intact. They believe that some bacteria can naturally produce poison, particularly in stagnant water.

Elephants Without Borders (EWB) is a wildlife conservation charity that first flagged about these mysterious deaths. Their confidential report with references to 356 dead elephants was leaked to the public media in early July. The charity suspected that the deaths were not restricted to any specific age group or gender and has also highlighted that many live elephants have shown signs of weakness, lethargy and even disorientation.

Presence of green lush vegetation and the fact that waterholes in the vicinity are still full of rainwater eliminates the possibility of deaths due to dehydration or starvation. Though the blue green algae can be deadly when consumed along with water, elephants generally drink water from the middle of the water bodies, but not edges. But there has been a pre-historic mass elephant deaths due to Cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) and this cause could only be substantiated with the laboratory results, which is still underway. The neurological symptoms like walking in circles suggests that anthrax poisoning is also a possibility.

The Anthrax bacteria occurs naturally in soil and elephants become infected if they have ingested contaminated soil or breathed in. Anthrax is known to be affecting wild life and domestic animals around the world.

Experts opinionated that it requires a detailed sampling of carcasses, soil and water in the delta area for an accurate explanation. But the challenge is the remoteness and the hot weather in the area which could have degraded the body, erasing important evidences, and scavenging animals which may eat organs making it extremely challenging for the examination. Despite the wildlife conservationists’ huge cry worldwide, there is still no confirmation on the absolute cause for the hundreds of elephant deaths.

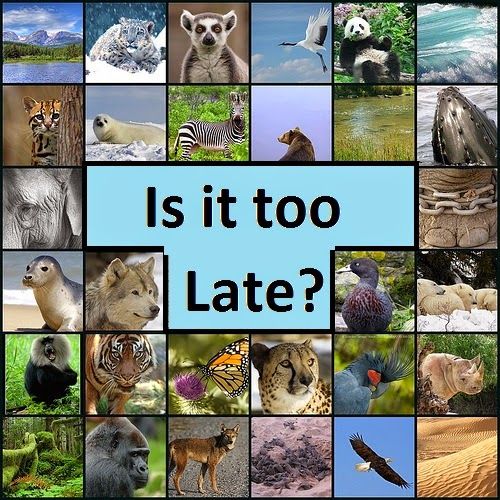

This is the introduction to a series on animals that are endangered or in decline, giving them a name so that we can give them a voice.

A.E. (Anthony) Lovell

Bigodi wetland sanctuary, Uganda, 2017.

Bigodi wetland sanctuary, Uganda, 2017.

The Village Weaver is one of the most common, widespread weaver species. It is larger than most weavers, with red eyes in both sexes and a heavy black bill. The breeding male has the head mainly black, the nape, hindneck and breast below the black throat are chestnut. The back is spotted yellow. The breeding female is yellow below, and whiter on belly. The non-breeding birds are duller than the breeding female.

The Village Weaver inhabits bushy savanna, riverine woodland, wetlands, cultivated areas, rural villages, urban and suburban gardens, and villages and clearings in the forest. It is frequently associated with human habitation in west and central Africa. It is absent from arid regions, dense forests, and miombo woodland.

Its diet is seeds, including grass seeds and cultivated cereals. It is regarded as a pest in rice-growing areas, and also damages maize, sorghum and durra crops. It also feeds on fruit, nectar, and insects, such as beetles, ants, termites and their alates, grasshoppers, mantids, caterpillars, and bugs. It forages by gleaning vegetation, including tree trunks.

The Village Weaver is gregarious, being found in large flocks and in the non-breeding period joins large communal roosts.

It is highly colonial, with more than 200 nests in a single tree and colonies in excess of 1000 nests. The Village Weaver is polygynous, with up to five females simultaneously on the territory of a male, and up to seven during a season. Females may change mates in a season. Larger colonies appear to be more attractive to females, with a higher proportion of females per male.

When females enter a colony, males hang below their nest entrances while giving nest-invitation calls and flapping their wings to show the yellow underwings. The nest is spherical, sometimes with a very short entrance tunnel. The nest is woven by the male within a day, generally from strips torn from reed or palm leaves.

The male often includes a ceiling layer of broad leaves. The female lines an accepted nest with leaves, grass-heads and some feathers. Nests are suspended from drooping branches. A single male may build more than 20 nests in a season, and unused or old nests are regularly destroyed to make space for new nests. Empty nests may be occupied by other animals, including snakes, wasps, mice and bats, and nests may be used for breeding by a wide variety of species including Cut-throat Finches.

The eggs are white, pale green or blue, either plain or variably marked with red-brown speckling. Incubation is by the female only, for about 12 days. The chicks are usually fed by the female alone, but males in some parts help. Female Village Weavers recognize their own egg pattern, which is constant throughout her life, and discriminate against non-matching eggs. Nest predators include snakes, especially boomslang Dispholidus typus, monkeys and baboons, crows and raptors.

The longevity record is 14 years in the wild.

#Birdifeastafrica

#Earthshots

#Visitugandarwandatanzania.