From tigers in Asia to elephants in Africa, wildlife crimes only seem to make the news when it concerns rare and exotic species and high-value animal parts like rhino horns.

But there’s no need to cross the ocean to find the pervasive and persistent problem of poaching and links to an international black market. Poaching for specific high-demand animal parts to feed the demand of a nefarious underworld of dealers, merchants and buyers is widespread in the U.S., its fingers extending to nearly all parts of the country.

And with any criminal enterprise, it’s the money that supplies the motive. For example, the American black bear has long been poached for its hide, paws, gallbladder, and bile, mainly due to their use in Eastern medicine. (Gallbladder and bile are often used to treat diseases of the heart and kidneys.) Undercover operations have found single dried bear gallbladders fetching as much as $30,000 on the black market.

But it’s not just the American black bear that’s under siege. The horns of ram sheep can sell for more than $20,000 on the black market. The bighorn sheep, which largely resides in the area between the San Jacinto Mountains and the U.S.-Mexico border, has been on the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service’s endangered species list since 1998. Although land development and disease have been the major contributors to the dwindling of this species, poaching is only putting more nails in the coffin. These sheep are usually found in remote areas, making it a challenge for game wardens to patrol and monitor poaching activity.

Shark fins are also highly valued in Eastern cultures, making poaching off the coast of California a major problem, despite the fact that selling or distributing shark fins is illegal under California’s Shark Fin Law. When a great deal of money is at stake, the crimes continue. A single shark fin can sell for $500 in China, where it is used to make shark fin soup, a delicacy. It is estimated that there are more than 100 million shark deaths every year due to shark finning: the practice of catching a shark, slicing off only the coveted fins, then tossing the animal back overboard to die a slow and painful death To read the full article visit: gamewarden.org

We have a serious problem of illegal hunting in the U.S. and the NRA is NOT holding their original standards which was about gun SAFETY AND TRAINING. NRA became the only national trainer of law enforcement officers with the introduction of its NRA Police Firearms Instructor certification program in 1960. In civilian training, the NRA continues to be the leader in firearms education. Over 125,000 certified instructors now train about 1,000,000 gun owners a year. Courses are available in basic rifle, pistol, shotgun, muzzleloading firearms, personal protection, even ammunition reloading. Additionally, nearly 7,000 certified coaches are specially trained to work with young competitive shooters. The focus now is more about fighting for gun rights, money and political power. Safety means nothing to the NRA. By the NRA getting away from their roots has created a very dangerous gun problem in the United States.

Another problem in the U.S. is Texas

Of the 1,525 seizures that FWS recorded at the U.S.-Mexico border from January 2020 to September 11, 2023, more than 85 percent occurred in Texas, accounting for 17,317 animals and exotic animal parts—such as a South African ostrich and shark bones. Learn more here:

The biggest organization that is a threat to our wildlife is Safar Club International with their trophy hunting AND Hunting contests! Learn more at

To read about Wildlife Crime and Corruption in the U.S. follow Cami Ciotta's newsletters at linkedin.com

To support our fight to educate people the need to protect our wildlife please donate $5.00 at wildlifebroadcast.com

or visit our store and make a purchase at mojostreamingwildlife.com

Thank you for your support and to be a part of the movement please sign up at Sign Up - MojoStreaming.com

A Note from Chris Jim who found a unique way to support his family.

My name it's Chris Jim, I was born in Zimbabwe on 12/04/1976. I am the last born of a family of 8. My father Andria Jim died when I was 3 years so I was raised by my mother Maria Kim and my elder brothers. My brothers used to make cars and pushing toys out of wire, that's when I started and they taught me how to make my cars from wires. When I went to school I started to attend craft lessons from then it was my passion to make anything from wire. Still at school during weekends I used to go and sell my wires in the streets of Harare to the tourists. When I finished school there were no jobs at home so I kept on making my wire art and selling in the streets from there I didn't look back till now I am surviving from my art works. I am living in South Africa in Johannesburg, I am married to Janet Fire, and we are blessed with 3 children, Ashley, Andrew and Adrian Jim. I am teaching them how one can create jobs from art.

Thank u for supporting my work, Please visit: mojostreamingwildlife.com USE CODE FreeShip for free shipping and save $40.00 until December 23, 2023 Allow 10-14 days for shipping

Regards Chris Jim

An alien civilisation coming across our solar system would name our planet Ocean, for most of Earth is under water. Being air-breathing and living on the bits that stick out, we mostly regard the vast liquid blue that surrounds us as a beautiful but often scary “other”. Billions of us, however, rely on it for food. This is part two of a series about the relationship between the creatures below the sea’s surface and the people in boats who catch them. Read Part One

Through a friend in 2011, Oliver Godfrey met Gary McFarlane, the then Port Elizabeth-based skipper of a demersal shark long-line boat called White Rose. When one of the crew was fired, he was offered a job. As a young photographer interested in wildlife, the chance to do some trips with him was appealing, so Oliver joined up on nine week-long trips. The next two months of shark catching would traumatise him for the rest of his life.

“Gary called himself Shark Slayer and he was that for sure,” Oliver told me after years of remaining silent about his experience. “They were fishing between PE and De Hoop further west. Every trip – and I did nine or 10 – they were (tonnes) of sharks. Smooth-hounds, soupfin sharks, disallowed species such as ragged-tooth sharks, hundreds of spotted gully sharks and hammerheads, including hundreds of pregnant sharks.

“Three great whites got entangled in the long-lines and killed while I was on board. The guys were indiscriminate. Hundreds of seabirds were hooked and killed – gannets, cormorants, albatrosses. There was big bycatch that was discarded dead. They were fishing next to – and I’m sure in – Marine Protected Areas [MPAs].

“I hung on longer than I should have to document what was going on, but I can tell you I ended up so broken by the massive carnage, the cruelty. Traumatised, depressed.

“I needed help to get the story out, but nobody would help. I was advised to drop it. I had all these photographs. They knew that and I got frightened. Then I had three break-ins in two months. My hard drive with the pictures was stolen.

“For years now I just left the story lying there. But it needs to be told because the killing hasn’t stopped; the great whites are almost gone. And some of the images were saved to the cloud as proof of my story. So now I’m telling you.”

That was how this story began. Could Oliver’s story be corroborated? The ocean is large, the Department of Forestry, Fisheries and the Environment (DFFE) does not place observers on these boats; there are no snoopy members of the public out there in the empty sea; crews are dependent on skippers for jobs so won’t talk. You can pretty much do as you please ... which is why information from an “insider” like Oliver is rare and valuable.

There are around 535 species of sharks in the world, one in three listed as vulnerable, endangered or critically endangered. My checking began with the apex predator poster-fish: great whites.

Despite being protected in South Africa, they’re missing in action, collapsing a billion-rand cage-diving tourist industry. Why? Four reasons have been suggested by a range of sources:

Let’s begin with the orcas. When the shark cage-diving industry in Gansbaai crashed for want of viewing great whites in 2017–2018, two orcas, Port and Starboard, were blamed. Five white sharks, their livers bitten out in a way typical of orca predation, washed up in Gansbaai. Culprits found and convicted.

But then a study by University of Exeter scientist Robin Fisher noted that white sharks had started declining in Gansbaai in 2013, before the arrival of the two orcas, which had simply added to the problem. It was more likely, he said, that the orcas, which before had not predated on white sharks, were doing so because of the overfishing of pelagic fish stocks.

So orcas may have moved inshore where they started preying on white sharks. However, the decline of white sharks in False Bay, starting in the early 2010s, actually matches the increase in effort by demersal shark long-line boats. As smaller sharks are also the whites’ main prey, this and not orcas, said Fisher, was likely to have precipitated their population to crash.

A later study (discussed below) would confirm that whites began declining in Gansbaai and False Bay before the orcas arrived.

So could the problem be over-fishing? Sharks are caught in massive numbers worldwide – one study put the number at anything between 63 and 723 million hooked a year. A study by TRAFFIC on trade dynamics put South Africa’s export of shark meat between 2012 and 2022 at 14,000 tonnes.

Great whites, being apex predators, are relatively few in number – a study done by Alison Towner in 2013 estimated there were around 900 white sharks left in South Africa, while Dr Sara Andreotti of Stellenbosch University put that number in 2016 between 353 and 522. By fish standards that’s not many.

They’re very general hunters but have a selective preference for other sharks. A study of the stomach contents of 591 whites confirmed their main prey was smaller sharks such as bronze whalers, smooth-hounds and soupfin sharks, which were being targeted by long-line boats based in Gqeberha. They belong to three companies, Fisherman Fresh owned by Sharmilla van Heerden, Letap Fishing owned by Imraan Patel and Unathi Wena, whose MD is Tasneem Hajee. All are no strangers to controversy. Calls to all three were not returned and a list of questions to Van Heerden were not answered.

Unathi Wena and its boat White Rose are currently involved in a court case in Bredasdorp Magistrates’ Court charged with fishing in a MPA. In 2014 Fisherman Fresh, was charged with illegally exporting 95 tonnes of shark and octopus to Australia, the sharks to be used in sales of fish and chips. Van Heerden was eventually acquitted.

For many years members of the public have reported seeing the Gqeberha long-liners prowling around MPAs (and occasionally in them), pulling out thousands of sharks. Every now and then a reminder comes ashore. In 2018, shark heads began washing up on the beach at Kanon Rocks and the boats White Rose and Mary Ann appear to have been the source. In 2020 a pile of headless, gutted sharks past their sell date were found dumped on Strandfontein beach in False Bay.

In May 2019 the White Rose was caught allegedly fishing illegally in the De Hoop MPA. In the same month a second vessel, the tuna long-liner Prins Willem 1 was also arrested when it docked in Port Elizabeth. It had allegedly been illegally fishing in the Amathole MPA off East London. In both cases, a total security of R400,000 was paid and the catches were released.

According to Chris Fallows of Apex Shark Expeditions, who has worked with great whites in South Africa for more than 30 years, “in the late 1990s DFFE gave out demersal shark long-line permits and fishing for sharks in [False] Bay rapidly increased. By the mid to late 2000s we noticed a slow decline of white shark sightings at Seal Island, nothing drastic but an overall down trend.

“Suddenly, around 2010, three boats started fishing the resource hard. They learnt how, where and when to target the smooth-hound, soupfin, bronze-whalers and hammerhead sharks. Their technique was highly focused and localised to sites where these species gather. They deny catching hammerheads because they’re protected, but they do and we have evidence. Oliver got pictures.

“Their catches soared and our sightings of white shark in False Bay went through the floor. In a nutshell, there are no longer enough smooth-hounds and soupfins left in False Bay to sustain the white sharks for the eight months of the year they’re not at Seal Island.

“Add to this the octopus fishery – which started in earnest around the same time targeting the key food source of smaller sharks – and you have a double whammy.”

Department of Fisheries scientists knew these sharks were racing towards crisis point. They openly acknowledged that even if all fishing for these species stopped, the soupfin shark stock could not be sustainably fished even by 2070.

A report issued by Fisheries in 2021 said that “at current catch, the soupfin shark is likely to be commercially extinct in 20 years. Fishing pressure is also already too high on the smooth-hound shark. Given that a maximum of four vessels have been active and fishing at any point in time, the state of the soupfin and smooth-hound shark stock cannot sustain an increase in effort”.

The report added another concern: “There is a health concern related to sharks being consumed. Sharks over a certain size (12kg ~ 130cm total length) are not safe to consume due to high levels of accumulated methylmercury and arsenic (among others). For some species (predatory sharks like mako sharks and sevengills) it is likely that no sizes are safe to consume at all.”

While the department introduced slot limits (not to catch younger or more mature animals), their own research told them this alone would not be enough. For instance, in 2010 the department reported annual catches just by demersal long-liners of soupfin at 106 tonnes and smooth-hound at 110 tonnes.

To be sustainable, the maximum upper limit for smooth-hound sharks was calculated at 75 tonnes annually from 2016 onwards; yet in 2019, the minister reported in Parliament estimated catch levels between 2016 and 2019 at one-and-a-half to three times higher than that by demersal long-liners alone.

Limiting tonnage a no-go

Because limiting tonnage would make the industry less profitable, it hasn’t been implemented. According to DFFE scientists who spoke to me off the record, this is presently totally unsustainable. The 2023 Parliamentary debate on fisheries can be accessed here.

Here’s the thing: even though smooth-hound sharks are considered by the DFFE’s own stock assessment as endangered and soupfin as critically endangered, they are still kept on the target species list of the official permit for demersal shark long-liners with no maximum catch limit. However, growing concern may be reflected in that by October 2023 only one demersal shark long-line licence had been allocated.

Of course, those sharks are also caught as bycatch in other fisheries and by surf anglers and the final catch weight or composition is anybody’s guess.

But who’s watching? There are no fisheries observers on those shark boats, catches are only occasionally checked and the DFFE mostly relies on the commercial logbooks entered by the same boats to track catches.

According to Oliver, “when a catch was being offloaded at the port, there’s not a chance that every single specimen was inspected. It’s bullshit for DFFE to try to claim that. I don’t think the inspectors really knew what was on the catch list or off it. They just processed the paperwork, took the skipper’s word for it, and off the catch went to Australia.”

The great white problem may not be just about long-line fishing catching their prey. A parallel threat is along the beaches of KwaZulu-Natal – baited drum lines and shark nets, which do not only separate sharks from people, but are also devices aimed at killing sharks.

Despite being protected in South Africa, an average of around 28 white sharks have been killed by the Sharks Board alone every year since 1991.

According to Fallows: “On top of that source of mortality, when shark scientist Charlene da Silva of the Fisheries department did a test near Gqeberha with three demersal long-line sets they caught two great whites and killed one.”

“Let's do the maths,” renowned shark biologist Enrico Gennari tells me, sitting on the edge of his chair in agitation. “By the DFFE’s own numbers, three whites caught over three days means that in nine weeks (the time Oliver was on the White Rose) shark long-liners would have caught and killed more white sharks than what Oliver reported. So Oliver’s numbers are realistic. If we extrapolate what he saw to the average demersal shark long-line fleet of the last 10 or so years, it would equate to an average of 50 to 60 white sharks killed every single year”.

“When you add this to what the KZN Sharks Board kills, you have nearly 100 whites a year being taken out of an estimated population of at most 1,000, or maybe even half of that.

“Great whites reproduce very slowly, only a few pups a year. At best, a 10% annual loss on a population of 1,000 is unsustainable. And that’s likely why we start to see a decline year on year since the early 2013, after the increase in effort by the demersal shark long-line fishery.

“Of course the orcas added to the problem,” says Fallows, “but elsewhere, when orcas kill white sharks, they move away but come back. They don’t disappear. Here they have. It’s because their population is crashing”

A 2023 research paper in Ecological Indicators led by Dr Matt Dickens of the KwaZulu-Natal Sharks Board and a group of other scientists favours the redistribution theory. The paper, using what Gennari describes as simplistic inferences, claims the orcas chased great whites up the coast, but that their population is “pretty stable”.

“Their population status appears largely unchanged,” they write, “despite the substantial reduction in occurrence in False Bay and Gansbaai in the last five years. For the status of white sharks in South Africa to remain unchanged, the population must have redistributed along the South African coastline.”

Gennari disagrees. “White sharks are down in False Bay, Gansbaai, Mossel Bay. Maybe there are three to 10 in Plettenberg Bay and a shark cage-diving operator in Gqeberha tells me he just saw his first white shark this year in August. If all the sharks migrated up the coast, you should have had a big uptick on the KZN drum lines, but you haven’t seen that.”

That paper’s message suggesting the white population is stable with no reason for concern and echoed by the media, says Gennari, “is very dangerous and could sink the conservation of white sharks in South Africa forever”.

So where does that leave sharks in South Africa? The news is not good. “Fisheries are allowing the commercial fishing of endangered and critically endangered species,” says Fallows. “It’s unheard of. It’s like allowing gin trapping of wild dogs in the Kruger National Park.

“Our so-called ‘best managed fishery in the world’ – as DFFE claims – has ‘managed’ two species from vulnerable to endangered and from endangered to critically endangered. We’ve also lost our white sharks; we’ve lost our hammerheads.

“If this is the best fishery in the world, then the yardstick by which we measure these things is not merely low, it's subterranean. That’s really where we are. It’s disheartening.”

Back to Oliver Godfrey, the traumatised photographer on the White Rose. It’s likely what he was witnessing in 2011 was the beginning of the end of great whites on South Africa’s southern shores through direct white shark mortality and the demolition of their food source by four long-liners. If his story had been heard earlier, something might, just might, have been done to stop the decline. But it wasn’t.

“I come from a diving background. I absolutely love the ocean,” he tells me. “What I saw was totally, totally ruthless. I felt it was my responsibility to record this experience. At the time I was handing out information to people, but they just didn’t give a shit.

“There was no limit on the numbers caught or species size. They didn’t take the hooks out of bycatch they didn’t want, they just bashed the fish on the side of the boat or simply cut their head off to not waste time taking out hooks. The damage caused by shark long-lining is insane. It is absolutely fucking insane.”

It is clear that urgent action is needed. This includes the permanent withdrawal of the demersal shark long-line fishing permits and a switch by the Sharks Board to more modern and sustainable ways to protect bathers in KZN.

Meanwhile, the shark cage-diving industry is in freefall with no end in sight and the little fishing communities that it supported are hurting.

It is not just about white sharks, says Fallows. “They’re a poster species for all others of the ocean. If we can’t protect such an important creature so vital to South Africa’s tourism, then the rest of our seas are in deep trouble.” DM

This article first appeared on Daily Maverick and is republished here under a Creative Commons license.

Coming to MojoStreaming on November 1st just in time for the holidays. We will have a large selection of Wildlife Watercolors that you can print off and frame yourself! All for under $25.00! Choose your favorite, add to cart, print, frame, gift it or keep for yourself.

We will have special sales to where you can buy for under $20.00! Hint Hint like Black Friday. Here are just a few examples of what you will find.

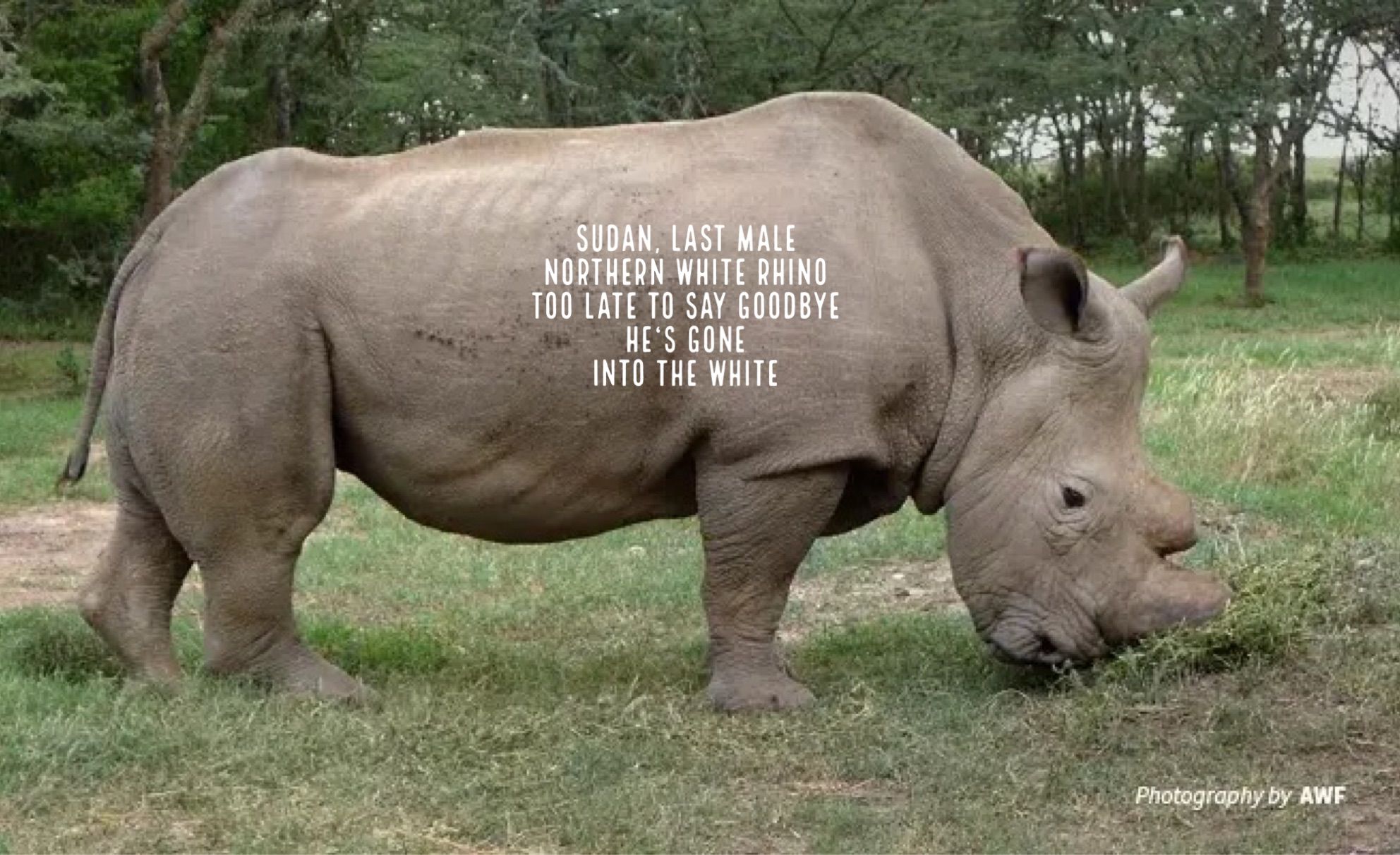

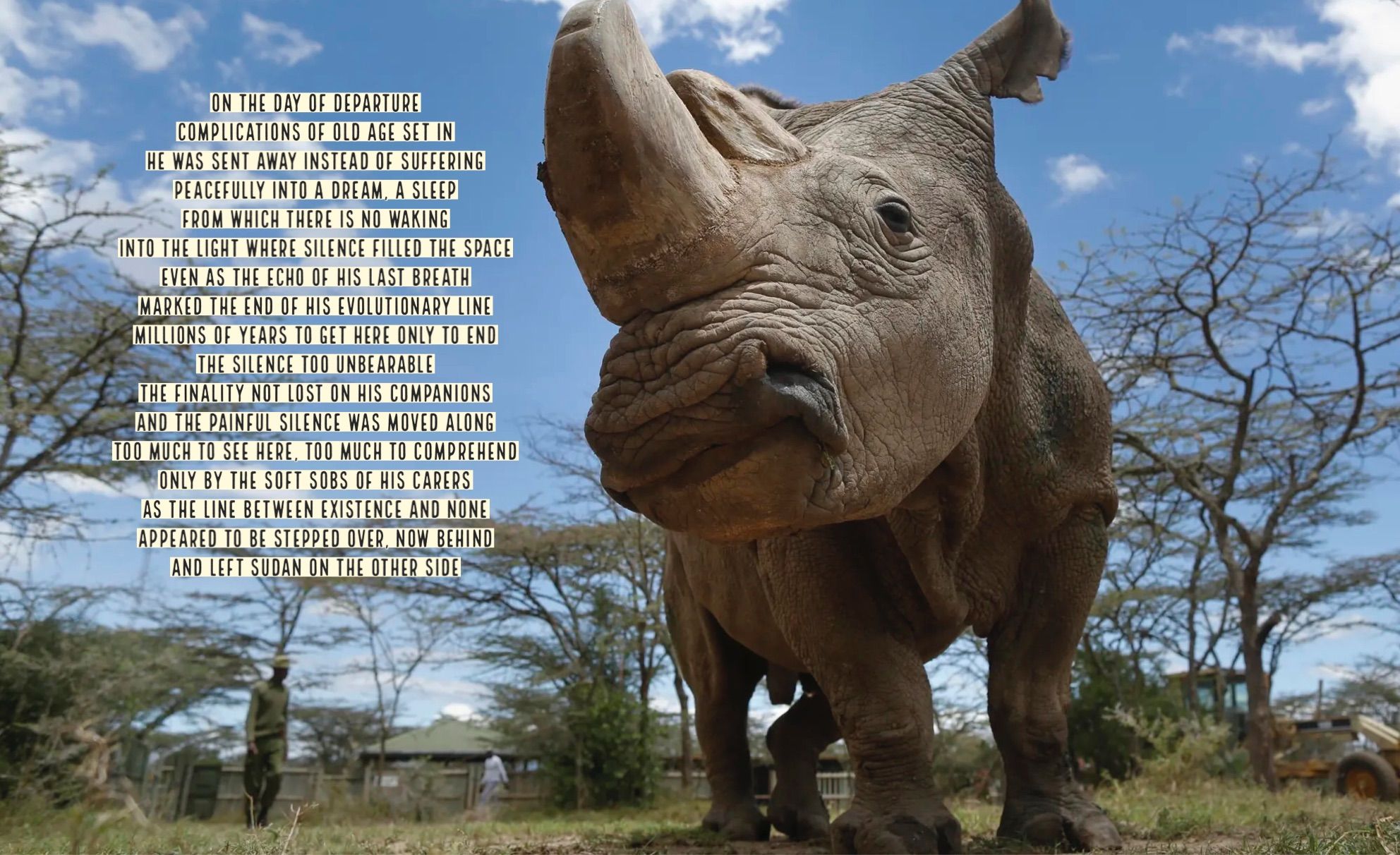

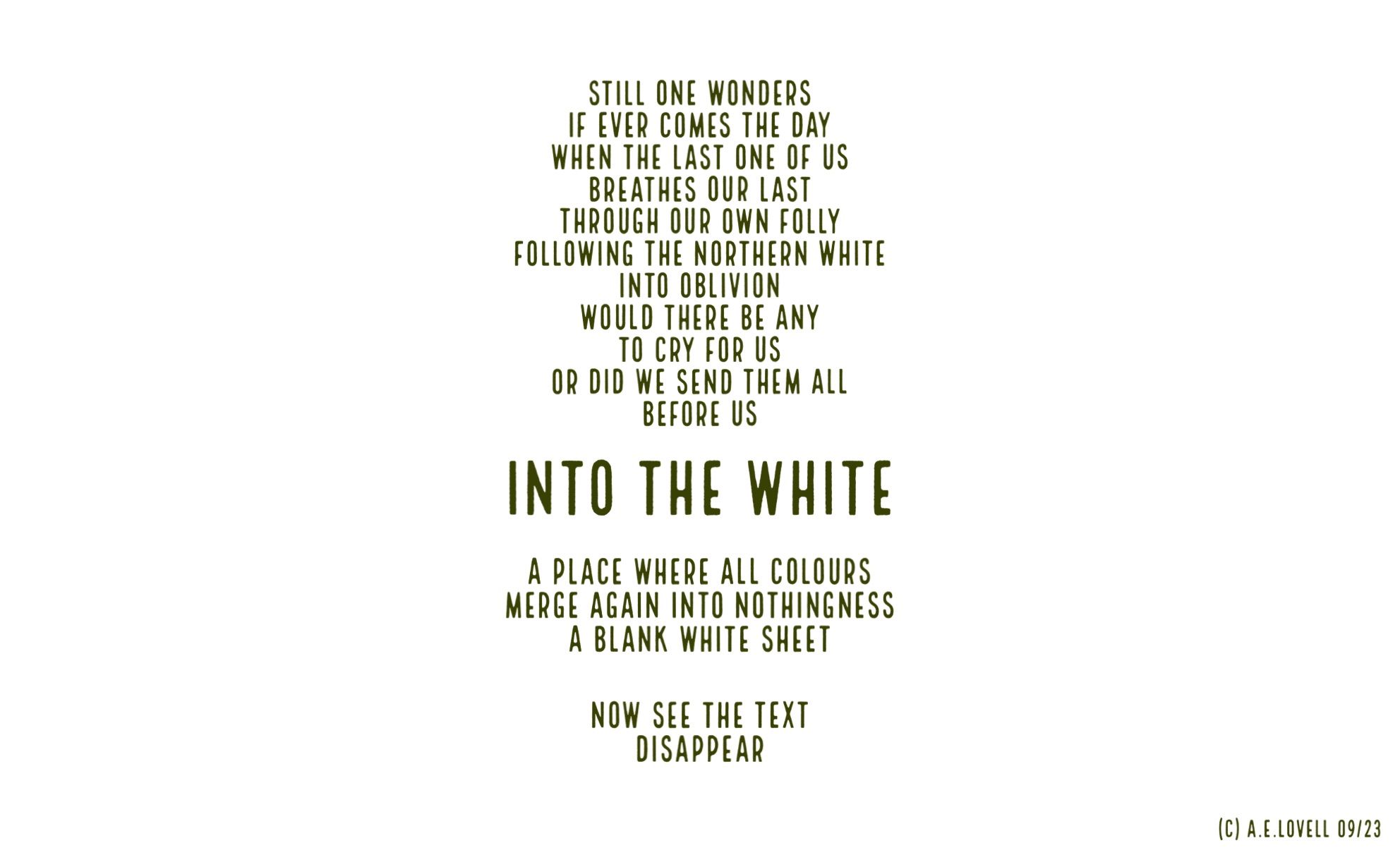

Second poem in the ‘Black and White, Wild and Wooly’ series for World Rhino Day - ‘Into the White’, Northern White Rhino (Ceratotherium simum cottoni).

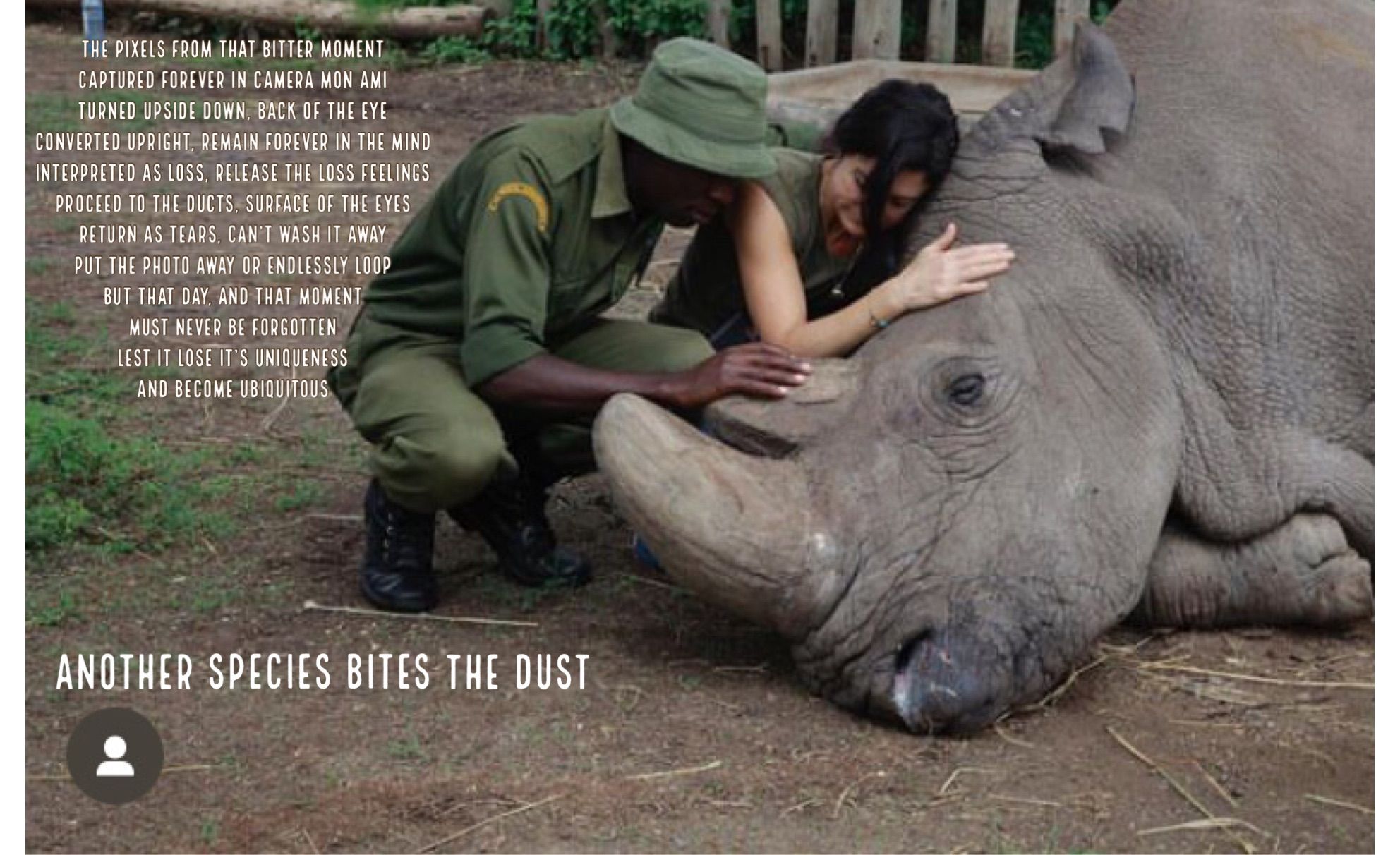

This was a hard poem to write based on a hard image to see - Ami Vitale’s haunting image of the last goodbye to Sudan, the last male Northern White Rhino. The name of the poem came easily, but the rest resisted all attempts for maybe 18 months. A couple of weeks ago I made the upcoming World Rhino Day a deadline to finish and publish it as part of this series.

My commentary is in the poem. Here is Ami’s (from her Instagram account)…

‘Saying goodbye to Sudan was one of the hardest moments of my life. On that day in March, 2018, we were witnessing not just the death of this majestic creature and the functional extinction of a subspecies, but also watching our own demise. We need to start recognising that our fate is linked to the fate of animals. Without Rhinos and all wildlife, we will suffer more than the loss of ecosystem health. We will suffer a loss of our own imagination, a loss of wonder, a loss of beautiful possibilities. I hope that this moment will mark a moment when humanity recognises how interconnected we all really are.’

Efforts are underway to rescue the species through genetic science, and several embryos have been achieved, with a view to one day finding a surrogate Southern White Rhino to re-establish the Northern White subspecies. If it does not succeed, there are only the two ageing daughters of Sudan still alive - Naijin and Fatu, being cared for and guarded by Ol Pejeta - functionally extinct and awaiting the inevitable.

Ami has made a film about Sudan - find details and the story of ‘The Last Goodbye’ on her website

#intothewhitepoem

#NorthernWhiteRhino #functionallyextinct